In this guest post from Jeff Drake, Catherine Chak, John Labovitz and Peter Oppitzhauser of Alix partners, the authors address the difficult commercial environment for offshore supply vessel operators, and suggest how the sector could reform itself to become more cost-competitive.

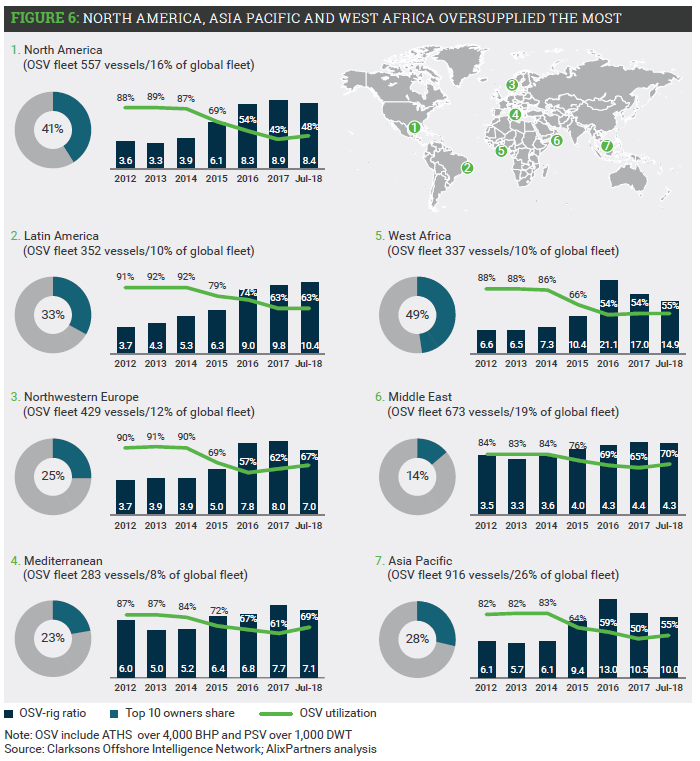

Warning lights continue to flash bright for offshore supply vessel (OSV) operators. Oil prices have rebounded to $70 to $75 per barrel, but the sector remains in serious trouble. Worldwide utilization is weak—with the worst-performing regions being North America, Asia Pacific, and West Africa.

Charter rates are still at or close to operating expense levels. The reasons for continued slowness include an oversupply of vessels caused by euphoric over-ordering during the boom and speculative building activity in shipyards across Asia due to supportive bank credit.

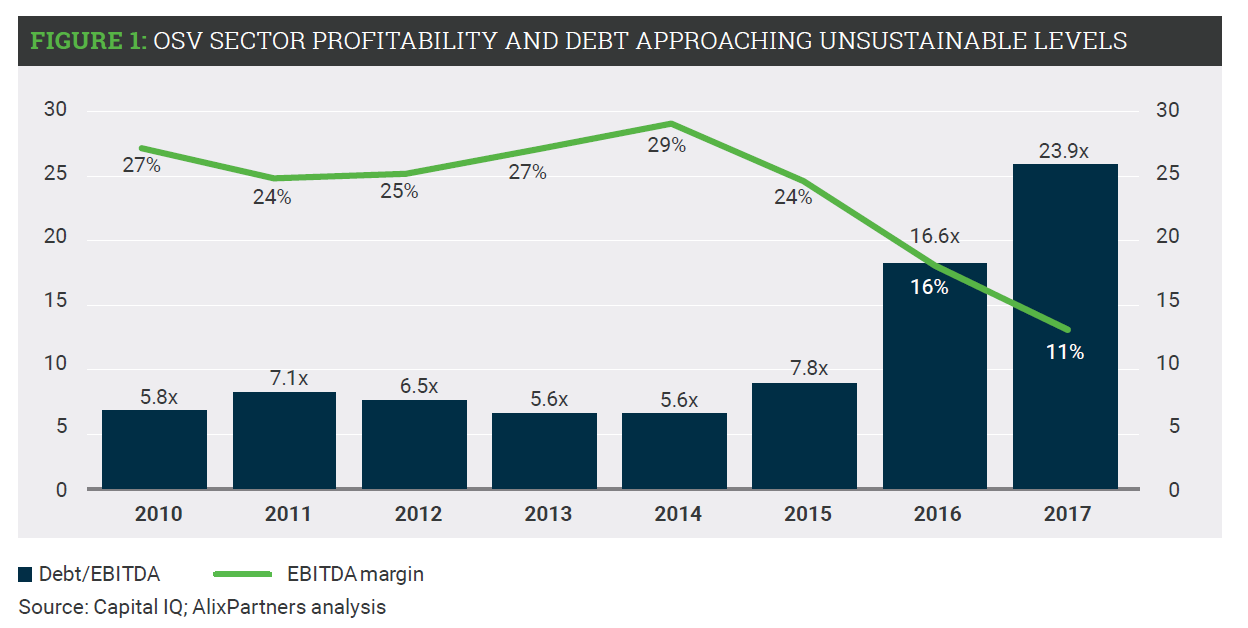

In addition, there has been a structural shift in demand due to the emergence of massive new supplies of shale oil in 2014. The financial consequences for operators have been devastating, with EBITDA margins shrinking and leverage ratios soaring to unsustainable levels (see figure 1).

OSV operators who hope to ride out the storm by expecting a further increase in oil prices to restore the sector to health are likely to have a long wait, and there is no assurance that their existing financial resources will sustain them through the downturn.

In an Altman Z-score analysis of OSV companies, a staggering 34 out of 38 were found to have scores of less than 1.8 in the trailing 12 months ended March 31, 2018. This indicates a high likelihood of bankruptcy for these companies within the next 12 months unless they take substantial steps to remedy their financial situation.

Too many vessels, too few active rigs

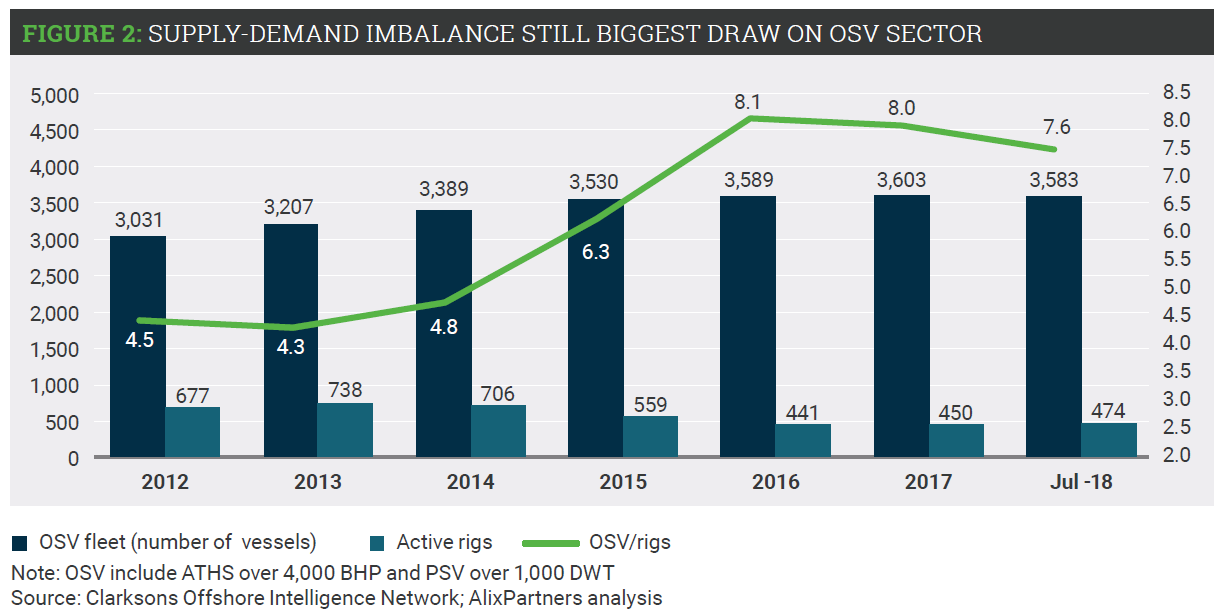

Rig utilization and day rates are two major components that drive revenue for OSV operators. The number of active rigs is currently 33% below 2014 levels, having declined from 706 in 2014 to 474 as of July 2018 (see figure 2), while OSV day rates are currently 40% below 2014 levels.

In the same period, the total OSV fleet has climbed from 3,389 to 3,583 vessels (see figure 2). The OSV-to-rig ratio stands at a less-than-healthy level of 7.6x, up from 4.8x in 2014. The oversupply of vessels is the single biggest drag on the OSV sector.

Shale has changed the game

Hopes for a sustained oil price recovery that will increase the number of offshore working rigs and consequently absorb the excess capacity of vessels do not seem especially well-founded, at least in the near-to-medium term.

The emergence of hydraulic fracturing as a feasible extraction technique has dramatically altered the oil industry’s cost basis. Offshore lost its status as marginal barrel to shale over the past few years due to its higher initial capital outlays and longer payback periods.

Geopolitical factors and US oil infrastructure issues aside, abundant shale oil supplies in the near term and the impact of energy transition on oil demand in the medium-to-long term will likely serve as constraints on drilling a substantial number of new offshore wells.

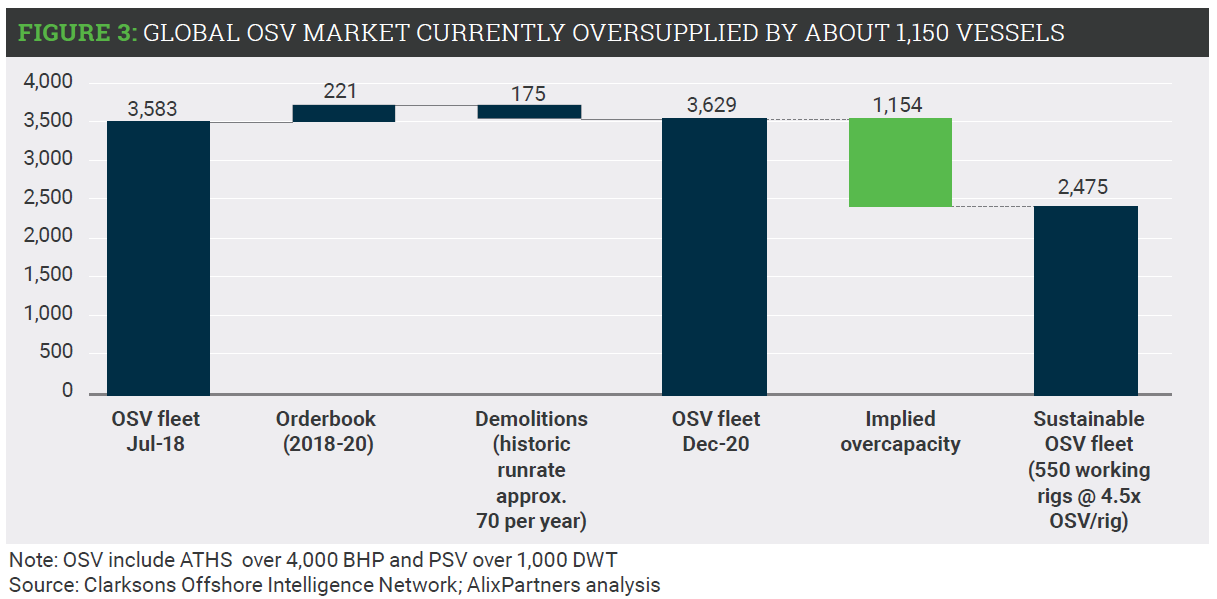

Given these structural shifts in the oil industry, the market consensus for future offshore rig levels is currently running at about 550. Assuming a 4.5x OSV to-rig ratio, this implies an overcapacity of about 1,150 vessels after factoring in current order book levels and demolition run rates (see figure 3).

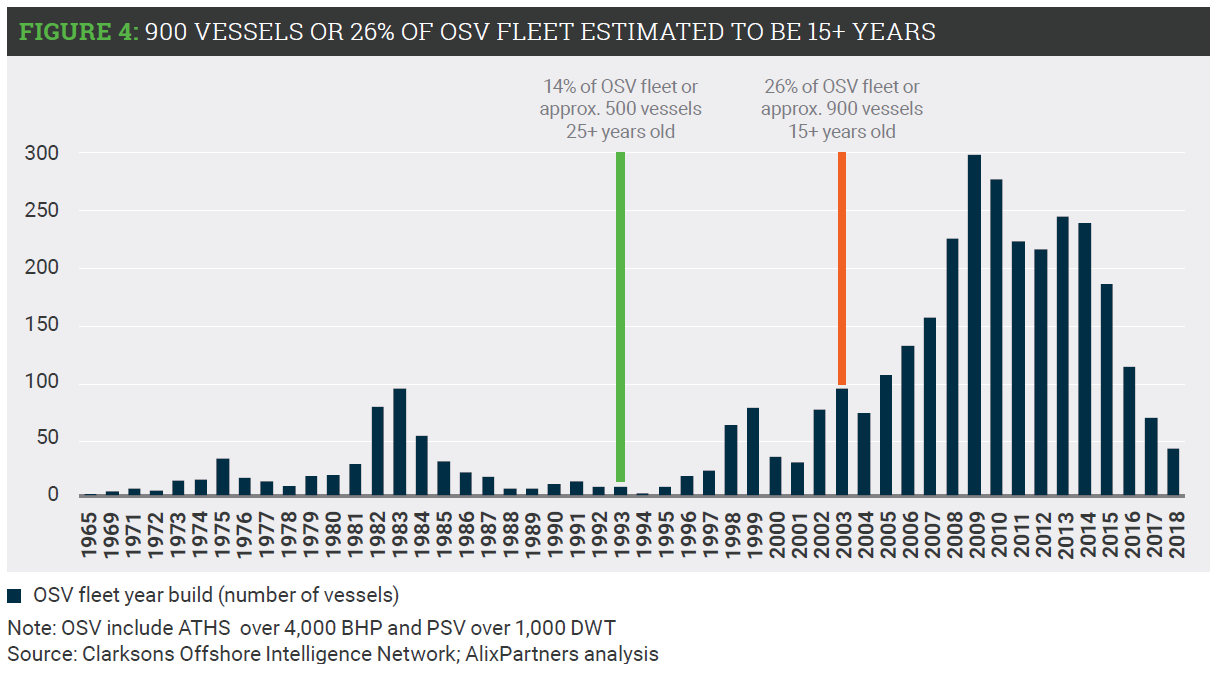

Indications are that vessels older than 15 years will have difficulty finding work as newer vessels are more efficient, less costly, and more compliant with increased environmental regulations.

It would therefore make sense to retire the roughly 900 vessels that are 15 years old or older, 500 of which are older than 25 years (see figure 4). But there are sizable impediments preventing the OSV fleet from adjusting expeditiously to sustainable levels.

Long supply hangover

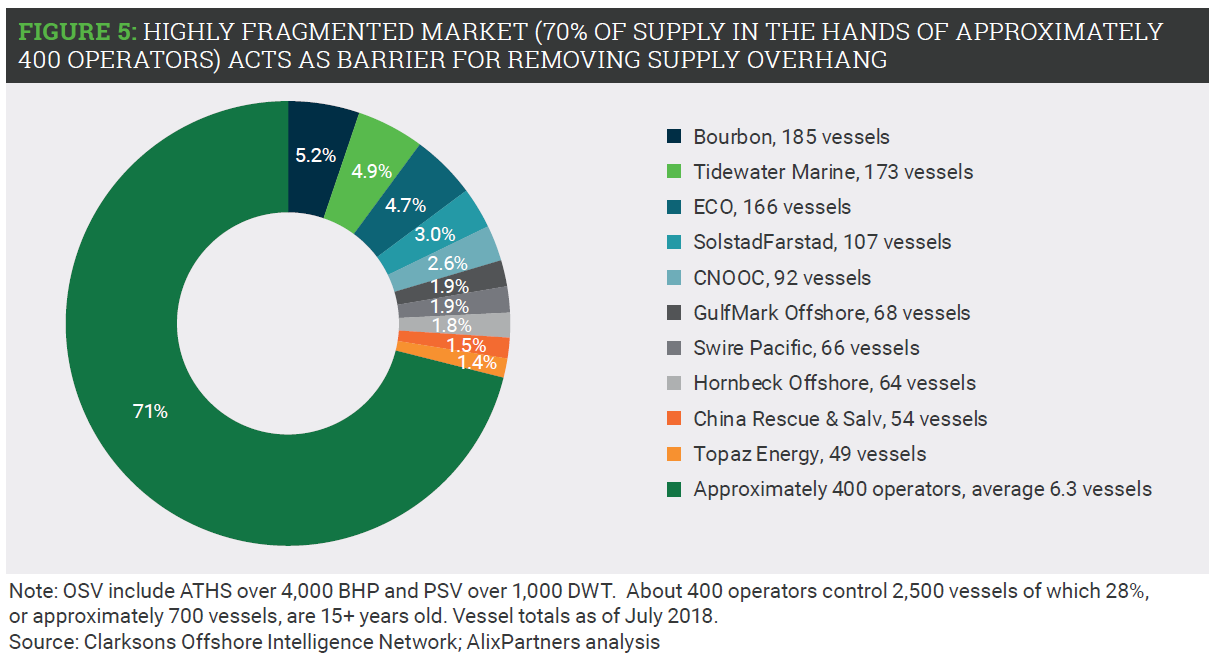

The most prominent impediment is the highly fragmented nature of the OSV sector. The 10 largest operators in the sector control roughly 30% of the total fleet, while the remaining 70%, or about 2,500 vessels, is in the hands of some 400 smaller operators, whose fleets tend to number six or fewer vessels (see figure 5).

These smaller operators have little incentive to retire any of their own fleets—unless the vessel is no longer viable to operate at a profit—and even less incentive to take collective action for the benefit of the sector as a whole.

In addition, there is a general bias among operators against retiring vessels altogether. Most prefer to stack the redundant elements of their fleets—which many operators have done with a third or more of their fleets— presumably in the hopes that demand will rebound and most of the vessels can be recalled to service.

Scrapping is the other impediment, as this option is not as economically attractive for offshore supply vessels as, say, for tankers or bulk carriers. The relatively low steel content of offshore supply vessels leaves even the largest of them with a scrap value of less than 1 to $2 million.

Transport costs to the final scrap location are the other limiting factor. Selling and transporting multiple vessels all together, for example by a semisubmersible heavy lift vessel, may bolster the financial viability of scrapping OSVs, as recently seen from Tidewater.

However, the economics of scale in transport costs may only be available to the biggest OSV operators unless smaller owners begin collaborating when making scrapping decisions.

The fleet percentage currently stacked is at about 26%, and the current debate in the industry centres around how this number may evolve. Arguably, a portion of the stacked fleet may not re-emerge in the market due to factors such as age, engine size, length of time spent stacking, class status, and failure to comply with environmental regulation.

Nonetheless, its presence continues to exert an influence on the supply-demand balance. This is because it only improves OSV spot rates, but does not fundamentally alter depressed OSV term charter rates.

In this environment, OSV operators, especially in Asia, North America, and West Africa, where the supply overhang is most acute, need to take a harder look at their options (see figure 6).

What is the way out?

At the moment, operators are price takers in the market at rates at or close to operating expenses. What is clear is that the winners emerging from this scenario will need to be highly cost-competitive, which will require operators to be more ambitious with their cost-cutting plans across their entire operations. Benchmarking can be a useful tool to assess what is best-in-class and set realistic targets.

Some more advanced operators are also using data and technology to get more efficient on both operating expenses and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses, for example by automating vessel operations and thereby reducing crew levels and associated costs.

Consolidation is also an opportunity to create stronger players that can stand out on their commercial strength, cost competitiveness, asset quality, management, and governance. The recent Tidewater and Gulfmark tie-up is a good example of consolidation driving cost synergies in the form of targeted SG&A cost reductions.

The financial distress in the sector and the saturation of young assets at fractional prices also presents a risk-reward spectrum, which could fall between highly attractive for the well-funded and optimistic, to ‘cheap for a reason’ for those with negative sentiments on the industry, such as a pessimistic outlook on how hungry the world really will be for oil.

When you run out of cash, you run out of time. Operators could have a liquidity plan and diligently identify keys risks that could prevent them from keeping the lights on. They need to act and avert any liquidity gaps, which may be done by selling assets, re-evaluating capital expenses, or restructuring debt with their lenders.

The decision whether to stack, scrap, idle, or sell vessels must be confronted with careful analysis, as each option has a different cash-flow profile. Balance sheet restructurings cannot be avoided as companies would have universally breached covenants and are likely not generating enough cash to cover operational costs as well as interest and principal repayments.

Companies need to engage with their banks, bondholders, shareholders, and new investors. For creditors, the restructuring topic is painful. The fact remains, though, that with a debt/EBITDA ratio of 23.9x, the sector is overleveraged, and most of that debt is unlikely to be repaid.

Never let a crisis go to waste. The difficult and painful actions that are required now to become more cost-competitive and restructure balance sheets could create stronger world-class companies that can not only survive this crisis, but even thrive if the sector recovers.

About AlixPartners

For nearly forty years, AlixPartners has helped businesses around the world respond quickly and decisively to their most critical challenges – circumstances as diverse as urgent performance improvement, accelerated transformation, complex restructuring and risk mitigation. These are the moments when everything is on the line – a sudden shift in the market, an unexpected performance decline, a time-sensitive deal, a fork-in-the-road decision. But it’s not what we do that makes a difference, it’s how we do it. Tackling situations when time is of the essence is part of our DNA – so we adopt an action-oriented approach at all times. We work in small, highly qualified teams with specific industry and functional expertise, and we operate at pace, moving quickly from analysis to implementation. We stand shoulder to shoulder with our clients until the job is done, and only measure our success in terms of the results we deliver. Our approach enables us to help our clients confront and overcome truly future-defining challenges. We partner with you to make the right decisions and take the right actions. And we are right by your side. When it really matters.

This article is reproduced with the permission of Alix Partners. It was originally published under the title “Too many ships, too few rigs: why recovery is still a distant dream, for the OSV sector.”

Join us at OPT, Europe's leading offshore pipeline technology conference.